Als zondagsblog deze keer een beschouwende analyse over de psychologie achter het klimaatdebat. Daar schreef ik al eerder over aan de hand van een column van de inmiddels welbekende Roos Vonk.

Arnold Fellendans stuurde me de onderstaande voortreffelijke analyse van de werking van het verschijnsel “groepsdenken”, zoals onderzocht door Irving Janis en op verschillende plaatsen op internet te vinden. Het is één groot feest van herkenning voor hen die al jaren proberen de waandenkbeelden van de alarmisten te bestrijden.

Grappig genoeg stuurde Arnold deze echter niet aan mij op om die reden, maar omdat hij ook wel eens dit soort gedrag bij sceptici meent te ontwaren! Dat maakt het artikel natuurlijk alleen maar méér lezenswaardig. Iets met de splinter in andermans oog en de balk in het eigen oog……

Graag krijg ik in de reacties van jullie voorbeelden van sceptische ”groupthink”. Dan kunnen we ons leven beteren!

Groupthink is ook noodzakelijk kwaad

Helaas is deze vorm van collectief ontsporen niet beperkt tot de klimaatdiscussie. Veel belangrijke structuren in onze maatschappij zijn er zelfs geheel op gebaseerd. Neem de enorme bedragen die er in iets grotere bedrijven besteed worden aan het “alle neuzen dezelfde kant op krijgen”.

En hoe kun je een land zonder dictatorschap bestuurbaar houden als je niet een soort algemene publieke opinie kunt mobiliseren? Zonder een gemeenschappelijk doel en een gevoel van groepsverbondenheid faalt elke samenwerking. Het is dan ook meestal de eerste stap naar de ontwikkeling van een arm land, om een gemeenschappelijke ideologie te creëren. Pas dan gaan de handen écht uit de mouwen en worden samenwerkingsverbanden productief.

Ik wil zelfs zover gaan te stellen dat dit gedrag diep in ons wezen verankerd zit en de basis vormt van de mens als sociaal wezen. En dat het juist daarom zo gemakkelijk is om zelfs grote groepen intelligente mensen volstrekt de verkeerde kant op te sturen.

Arnold Fellendans steunt niet alleen het idee dat dit gedrag in ons wezen verankerd is, maar hij onderbouwt dat in een artikel over ons ‘geloofvermogen’. Daarin behandelt hij onder meer de internethype en de kredietcrisis als voorbeelden van gevolgen van het sterke geloofvermogen van zeer intelligente mensen, zoals topmanagers van grote bedrijven en bankiers en hun toezichthouders.

Ook wetenschappers zijn sociale dieren.

Onderstaande voorbeelden tonen aan hoe verschrikkelijk dit mis kan gaan. De conclusie moet dan ook zijn dat het nuttig is om naar een gemeenschappelijke aanpak te streven, maar dat men als individu altijd zelfstandig en kritisch moet blijven kijken naar het groepsproces.

Met het risico om elitair over te komen: ik vind dat dit met name geldt voor wetenschappers en andere hoogopgeleiden. Die hebben meer kennis en begrip van de werking van ingewikkelde verschijnselen, of moeten tenminste in staat geacht worden om daar kennis over op te bouwen. Daarbij worden ze vaak alleen al om hun status beschouwd als opinieleider. Het verkondigen van een mening als expert brengt de verantwoordelijkheid met zich mee om altijd uiterst kritisch te blijven naar de denkbeelden die in de eigen groep ontstaan en vaste bodem vinden.

Groene Rypke de Duurzaamste

Voor degenen onder jullie die bij het lezen van de vaak verbijsterende verhalen van Rypke wel eens denken: “Maar hoe kan dat nou, één bekeerde Wageninger die het opeens allemaal beter weet dan hele instituten?”, is dit een wake-up call.

Als er iets gevoelig is voor groepsdenken, dan is het juist het soort instituten, waar hij tegen in het geweer komt, waarvan de leiding een eigen (soms niet eens) verborgen agenda heeft.

Helaas zijn de onafhankelijke kritische denkers juist altijd eenlingen.

Denk dus goed na vóór je om deze reden een kritisch verhaal terzijde schuift!

Directeuren zijn eindverantwoordelijk

Onderstaand verhaal lijkt vooral bedoeld als handvat voor hen die leiding geven aan groepen waarin dit verschijnsel op kan treden. Daarom draag ik dit blog op aan de Dijkgraven, Haaken, Hajers en Stamannen van deze wereld. Zij hebben enorm veel invloed op de manier waarop er in hun instituten gedacht wordt, en kunnen het verschil maken tussen ontsporen en op koers blijven. Ik neem aan dat ook zij bij het lezen van deze analyse flink wat momenten van herkenning zullen ervaren.

En ik hoop dat ze iets zullen doen met de aanbevelingen!

.

.

‘Groupthink’

Theorised by Irving Janis

Groupthink is a concept that was identified by Irving Janis that refers to faulty decision-making in a group. Groups experiencing groupthink do not consider all alternatives and they desire unanimity at the expense of quality decisions.

Group communication involves a shared identity among three or more people, a considerable amount of interaction among these people, and a high level of interdependence between everyone involved. It is essential to understand group dynamics for a variety of reasons. Everyone participates in groups throughout the course of a lifetime, and these groups are often very goal-oriented. The business community, non-profit organizations, and governments all use groups to make decisions. Sometimes this condition known as Groupthink can occur in groups that are extremely task-oriented and goal-driven. Groupthink is as “a mode of thinking people engage in when cohesiveness is high”. Groupthink leads to poor decision making and results in a lack of creativity. Although Groupthink has been studied extensively, many people are unaware of its dynamics and the consequences that they might induce.

It is the one of the most severe problem in our society. It is a serious mental disease that has not been recognized as such. It turns members of a group into believers and followers of rituals. They believe the group is right and others are wrong. It reduces communication from the group to outsiders. In serious cases of group-think, members use force and violence to convince non-believers.

Eight Main Symptoms of Group Think

- Illusion of Invulnerability: Members ignore obvious danger, take extreme risk, and are overly optimistic.

- Collective Efforts to Rationalization or Discount Warnings: Members discredit and explain away warning contrary to group thinking.

- An Unquestioned Belief in the Groups Inherent Morality: Members believe their decisions are morally correct, ignoring the ethical consequences of their decisions.

- Excessive Stereotyping: The group constructs negative stereotypes of rivals outside the group.

- Direct Pressure on a Member for Conformity: Members pressure any in the group who express arguments against the group’s stereotypes, illusions, or commitments, viewing such opposition as disloyalty.

- Self-Censorship of Deviations: Members withhold their dissenting views and counter-arguments.

- A Shared Illusion of Unanimity: Members perceive falsely that everyone agrees with the group’s decision; silence is seen as consent.

- The emergence of a Self Appointed “Mindguard”: Some members appoint themselves to the role of protecting the group from adverse information that might threaten group complacency.

Negative outcomes

- Examining few alternatives

- Not being critical of each other’s ideas

- Not examining early alternatives

- Not seeking expert opinion

- Being highly selective in gathering information

- Not having contingency plans

Irving Janis did lots of work in the area of group communication. He wondered why intelligent groups of people sometimes made decisions that led to disastrous results. Janis focused on the political arena. He studied The Bay of Pigs conflict, The Korean War, Pearl Harbor, The conflict in Vietnam, The Cuban Missile Crisis, makings of The Marshall Plan, and Watergate. Janis was puzzled by the inability of very intelligent people to make sound decisions. His answer was a condition he termed Groupthink.

Janis defines Groupthink as a “a quick and easy way to refer to a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action” . Janis further states that “Groupthink refers to a deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment that results from in-group pressures”

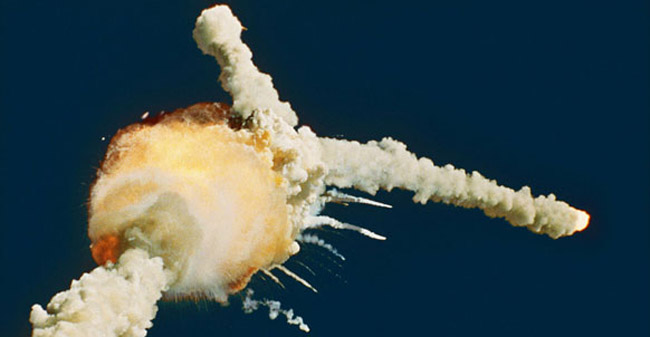

Challenger Launch

January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger blasted off from Kennedy Space Centre in Florida. Seventy-three seconds later it explodes. Inquiring finds that two rubber O-rings fail in the Solid Rocket Boosters.

The O-rings had been classified as a critical component “a failure point-without backup-that could cause loss of life or vehicle if component failed”. Engineers were concerned before the flight because O-rings had never been tested below 14.4°C and morning of launch had predicted temperature below freezing. Even with engineers concerns managers still pushed for a launch, creating a great example of ‘groupthink’.

1. Illusion of Invulnerability. NASA had almost perfect record causing group attitude of invulnerability.

2. Collective Rationalization. Misconception of backup O-rings was shared by management and never questioned.

3. Belief in Inherent Morality of Group. Engineers had impression that managers had changed morals.

4. Outgroup Stereotypes. Managers were rude and noncompliant with engineers.

5. Direct Pressure on Dissenters. Managers’ worry over NASA’s public view and future caused pressure on engineers decision.

6. Self-Censorship. Engineers censored their statements of conditions.

7. Illusion of Unanimity. Engineers concerns were not submitted to superiors.

8. Self-Appointed Mindguards. Flight readiness team did not receive O-ring experts’ views.

Other Famous Examples

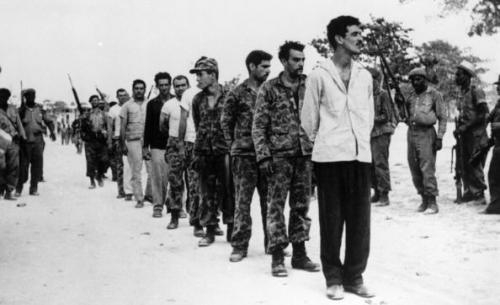

- Pearl Harbor Attack.

- Truman’s invasion of North Korea.

- Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs fiasco.

- Johnson’s escalation of Vietnam War.

- Nixon’s Watergate break-in.

Preventing Groupthink

Janis warns that preventing groupthink may open the decision-making process up to other errors, however it is still worthwhile trying. Whilst he theorizes that some knowledge of Groupthink can be dangerous in certain situations, it can certainly help make better decisions if the people are reasonable and aware that they should not fall victim. Decision making groups should avoid group insulation, overly directive leadership and some other factors that can encourage ‘premature consensus’.

The following prescriptions for preventing Groupthink are suggestions intending to help groups make better decisions. However they do not guarantee that a good decision will necessarily be made, the suggestions are intended merely to lessen the chances that Groupthink will occur.

- Each person in the group should be encouraged to be a critical thinker.

Create an atmosphere in the group that encourages people to express their ideas. One problem of Groupthink is that dissenters are either disregarded or ‘ganged up on’. Every member should be encouraged to raise any concerns they have with a proposal. The leader too must be able to accept criticism, without giving any disapproving feedback even by looks or facial expressions. Likewise, members should be sensitive to feelings.

- The leader should try to remain impartial to ideas or proposals so as not to influence those below him or her.

Often when a leader of the group expresses a preferred option, group members can be encouraged to seek agreement with him or her rather than critically evaluating all possibilities. The leader should not direct the group towards their personally favoured solution, and should be careful not to disregard comments made otherwise.

- Use several groups in parallel each with different leaders to work on the same problem.

Generally the different groups are more likely find different proposals the best. Likewise, different leaders will direct the group in different ways. So the possibilities and criticisms are more likely to be covered between the groups.

- Use several smaller sub-groups that then convene together as a larger group and then reach their decision.

Again the use of separate groups increases the chances of a better coverage of proposals and problems by the whole group. However, the groups should be careful not to adopt a ‘the others will do it’ attitude where they assume another group will have looked at a problem or other proposal.

- Each member of the group should sometimes discuss the group’s progress with trusted associates outside of the group (but within the organization) and convey their thoughts back to the group.

This gets some fresh ideas and views on the problem. It could even be discussed with an associate in a different group of the organization to gain a whole new view.

- Outside expert opinion should be sought.

Janis recommends this from colleagues although outside experts could also be used similar to an ‘external audit’ of the proposals. The outside experts would ideally check that nothing has been overlooked and pick up on anything that may have been missed or that they feel deserves more attention.

- Assign a devil’s advocate.

Essentially someone in the group should be assigned this role and their job as such is to critically evaluate proposals and question everything. This is only effective if they are not disregarded and also if they do actually perform this task. Otherwise, this can actually lead to more confidence in a bad decision because the group will feel that the decision was made with due consideration of criticisms.

- Spend time discussing and theorising any rivals possible moves or responses.

Time should be spent regarding possible responses or prior moves by rivals. It is important that the rivals are not assumed to be inferior or incapable. One possible way is for the group to come up with best-case and worst-case scenarios.

- Have a ‘second chance’ meeting.

After a consensus is reached but before a final decision is made, a second-chance meeting should be held. This should be presented as an opportunity for group members to express any lingering doubts or concerns with the consensus reached.

Sometimes this is more effective in an informal setting. The ancient Persians, and in Roman times the Germans also, apparently made a habit of reaching decisions twice- once sober, once drunk. Whilst getting drunk is not necessarily recommended, the idea of an open and relaxed meeting is.

As mentioned, these suggestions are not cures for Groupthink, they do not guarantee good decisions. However being aware of the Groupthink symptoms and with these suggestions in the back of one’s mind, a better outcome is more likely.

References

- http://sol.brunel.ac.uk/~jarvis/bola/communications/groupthink.html

- http://www.abacon.com/commstudies/groups/groupthink.html

- http://www.abc.net.au/science/slab/shuttle/challenger.htm

- http://www.afirstlook.com/archive/groupthink.cfm?source=archther

- http://www.asce.org/professional/leadership/emtechniques.cfm

- http://www.css.edu/students/lhamre/performing.htm

- http://www.swans.com/library/art9/xxx099.html

- Janis, Irving L.; Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. (1982)

- Moorhead & Griffin; Organizational Behaviour. (2001)

Tja Rypke, Greenpeace en PBL et al zouden dus headhunters op ons moeten zetten om ons te binden als interne kritische geest.

Ik denk dat groepsdenken soms niet meer te elimineren is. Het plaatje past ook perfect op mezelf. Ik ben een sceptisch groepsdier. Dat wil zeggen dat ik een natuurlijke neiging heb me tegen de meerderheid te verzetten (en daardoor ook gemakkelijker waarneem wanneer die meerderheid er naakt bij loopt als met de kleren van de keizer), maar dat ik toch ook de warmte en geborgenheid voel als ik met een groepje sceptici aan de borreltafel zit.

Met een parafrase op Rinus Michels zeg ik graag: klimaat is oorlog! Of: milieu is oorlog!

Wat mij betreft mogen al die instituten jou op de loonlijst zetten als kritische geest, maar dat helpt alleen als je moet bijsturen. Zoals dat cruise schip zeg maar. Dat er iemand in de hut staat die zegt: "kweenie, ietsje verder van dat eiland af misschien?"

Maar het kan natuurlijk niet dat Ajax een Feyenoorder in huis haalt als wapen tegen de eigen group think. Of een windmolenindustrie een Hans Labohm. Of Heiniken een geheelonthouder. Is toch wel lastig in de team motivatie op maandagochtend: "Jongens, windmolens zijn een grote leugen en puur weggegooid geld waarmee we ook goede dingen zouden kunnen doen, en dan nu aan de slag! Fijne werkweek weer!"

Nee ik geloof in Thomas Kuhn en zijn "in de tijd van de paradigmawisseling is er geen zinvolle discussie tussen de twee kampen mogelijk" (met de nadruk op het woordje "zinvol"). en daarom stem ik steeds af op Radio Oranje om te horen in hoeverre de bevrijding van buitenaf nadert…

oh sheer irony: de reacties op dit blog zijn een perfect voorbeeld van groupthink don't you think?

Er is niets mis met denken in een groep :-)

Het gaat mis in groepen waar (pseudo)intellectuelen de dienst uitmaken en door manipulaties volgers kweken en contributanten werven onder het zgn. "klootjesvolk"(zoals WWF, GreenPeace, religies, politieke/economische stromingen).

Dan gaat het niet meer om de realiteit of de waarheid, maar om ooit eerder geformuleerde doelstellingen te verwezenlijken.

Het doel heiligt dan de middelen.

Anti-klimaatalarmisten, zoals die zich hier manifesteren, vormen in die zin geen groep gezien de diversiteit aan achtergronden.

Wat ze gemeen hebben is de drang naar een antwoord op de vraag: is de essentiële kennis wel aanwezig die nodig is om ingrijpende maatschappelijke veranderingen te rechtvaardigen.

Groepsdenken: Het is evident kenmerk van / bij klimaat, milieu en duurzaam denken, en wordt versterkt door het subsidie systeem door de overheid.

Groepsdenken: Psycho-sociaal fenomeen, waarbij een groep van op zich zeer bekwame personen zodanig wordt beïnvloed door groepsprocessen, dat de kwaliteit van groepsbesluiten vermindert.Het is een denkwijze, die plaats vindt bij mensen, die nauw met elkaar samen werken, daarbij een hechte groep vormen en die zoveel waarde hechten aan een unanieme mening, dat deze unanimiteit belangrijker wordt geacht dan een kritische rationele instelling.

Symptomen: hechte homogene samenwerkende groep(-en),leiderschap via richtlijnen, Guru aanbidding, overschatting van eigen gelijk, kortzichtigheid, selectieve informatie verzameling, pressie op uniformiteit van het denken, incomplete en onoverzichtelijke doelstellingen, geen evaluatie van progressie, propaganda.

http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groepsdenken

Denken in een groep KAN misgaan door ons geloofvermogen en als er een dominante leider is. Kennedy stelde na de invasie in de Varkensbaai de regel in dat zijn adviseurs ook vaak genoeg zonder hem moesten overleggen, om zijn onbedoelde dominantie te voorkomen. Zijn opvolgers vonden dat alleen maar een dwaze gril.

De inzichten van Janis zijn m.i. bijzonder waardevol. Een ideale organisatie zorgt er voor een 'luis in de pels' aan te stellen, die goed te belonen en daar ook naar te luisteren. Vergelijk het met de functie van de hofnar of de 'devil's advocate'. Een andere mogelijkheid is om actief naar een 'second opinion' van buiten de organisatie te zoeken.

In de praktijk blijkt echter steeds weer dat dat erg moeilijk, zo niet onmogelijk is.

Anderzijds mogen we ook niet vergeten dat er dankzij groepsdenken vaak ook grootse dingen tot stand zijn gekomen.

@solon

Ik ben regelmatig bezig met skeptici te corrigeren over de CO2-cyclus en infraroodfysica. Zoals daar zijn Hans Jelbring, wijlen Ernst-Georg Beck, Hans Labohm en Arthur Rorsch, en ook op dit blog meen ik dat ik niet alles voor zoete koek slik wat mijn medebloggers presenteren.

Glasnost was de ondergang van de sovjet-dictatuur. Het IPCC doet er alles aan om de zeer gewenste openheid dichtgemetseld te houden.

Ik moet altijd bij dit soort groeps studies denken aan Top Gear.

Daar was die volgespoten Engelsman, Simon Cowel, een keer te gast. Die moest zoals alle sterren een rondje in de redelijk betaalbare auto. En toen zei hij tegen Clarkson de epische woorden; "De stig had je wel thuis kunnen laten. Ik kan hem nooit zo goed nadoen als hij zichzelf kan nadoen. Daarom moet ik een andere manier verzinnen die beter is.".

Daarom ben ik het ook met Hans oneens, de beste ideeën komen meestal van individuen en niet van groepen, omdat groepen vaak 'vast' zitten.

Kijk maar naar de EU als voorbeeld.

Is geld niet ook een factor welke het denken beïnvloed? Ik vraag me af of hier ook resultaten over bekend zijn, uit ervaring weet ik dat gras blauw is, giraffen zwarte en witte strepen hebben en noem alle onzin maar op als het om geld gaat. Een niet te onderschatten fenomeen denk ik.

Wat "sceptici" anders maakt is het ontbreken van een moreel verheven toontje, waarmee de gemiddelde politicus en hier wat ik trollen noem het wel even uitlegt aan de verdwaalde schapen, dat maakt ons anders, ook verschuilen wij ons niet gauw achter "consensus" en "peer reviewed" als de argumenten ze niet meer redden, argumenten en wetenschap is altijd de achterliggende gedachte bij de meesten hier, niet blind achter een geloof aanlopen. Ik heb de afgelopen 1,5 jaar een hoop geleerd hier, dat CO2 wel degelijk misschien een miniem rolletje speelt in het geheel, alleen weten we niet welke, laat staan dat je er consensussen of modellen op kunt baseren.

Op de middeleeuwse koninklijke hoven was de hofnar de onschendbare scepticus, de humorvolle spiegel, had spreekrecht en mocht de draak steken met adviseurs, hovelingen en bestuurders, en werd persoonlijk beschermd door de koning, maar werd beschimpt, bespuugd en uitgesloten door de kring van belangen hebbende koninklijke politieke adviseurs en door de betaalde hovelingen als ze de kans hadden.

Klimaat & milieu sceptici herkennen die situatie in de huidige tijd, echter het verschil is dat de koning nu mee heult met de belangen hebbende politieke adviseurs en betaalde hovelingen.

Ik heb net een boek over het onderwerp gelezen dat voor de auteurs van dit forum ook nuttig zou kunnen zijn. Want ik had de hele tijd het klimaatdebat in mijn achterhoofd en er zijn veel parrallellen. Leidt zeker tot nieuwe inzichten (over oa. groepsdenken, cognitieve dissonantie, pseudowetenschap …). Al was het maar om zelf niet in open vallen te trappen.

De ongelovige Thomas heeft een punt.

ISBN 978-90-8924-188-7

Interessant DaVince!. De ongelovige Thomas heeft ook een website: http://www.ongelovigethomas.be/

Over academisch groepsdenken: zie de inauguratierede van Bram Bad Breath Bregman, die nu 1 jaar bijzonder hoogleraar Klimaat en Zuurademigheid is in Nijmegen. Het schijnt dat studenten alleen achter in de collegezaal willen plaatsnemen

Wie het niet met Bregman eens zijn die zijn 'ideologisch gekleurd' en 'ontkennen de klimaatverandering'(mensen die klimaatverandering ontkennen bestaan helemaal niet, er bestaan wel ontkenners van een zinvol debat waarvan Bregman de meest extreme exponent is): iets met balk en splinter geloof ik, en marginalisatie van fatsoenlijke kritiek over klimaatgevoeligheid. Zo iemand mag studenten gaan indoctrineren/desinformeren met zijn linkse ideologie op basis van verdraaiing van het debat over klimaatgevoeligheid voor CO2.

Zolang linkse ideologen als Bregman met hun alarmistische selectie een blinde vlek houden voor hun eigen ideologie voor social engineering wordt het nooit wat met het debat. En altijd maar weer met de demagogie van het enge linksmens Naomi Oreskes komen aanzetten, en autoriteits-drogredeneringen als '95 procent van de wetenschappers'. Vergeleken met Bregman is Pier Vellinga nog redelijk

'De klimaatproblematiek ondervindt hiermee een kritische houding binnen desamenleving van mensen die worden gedreven door een ideologie die je kunt onderbrengen in ‘the Western Social order’ waarin het industriële kapitalisme wordt gezien

als brenger van onze welvaart35. Deze mensen worden in de volksmond klimaatsceptici genoemd, terwijl het hier eigenlijk gaat om ontkenners van de huidige inzichten in

klimaatverandering. Ook hier lijkt de geschiedenis zich te herhalen.

Al vanaf de jaren twintig van de vorige eeuw waren er vergelijkbare discussies over de geloofwaardigheid

van de klimaatwetenschap, nadat de mondiaal gemiddelde temperatuur sterk bleek te stijgen36. De verschillen tussen toen en nu is dat ten eerste de discussie plaatsvindt

omgeven door een oneindige hoeveelheid informatie en ten tweede het gemak waarmee

deze informatie verspreid wordt.

Deze ideologische stroming heeft haar wortels in de Verenigde Staten (vs) en is in de tweede helft van de twintigste eeuw overgewaaid naar Europa en ook naar Nederland.

Nog steeds zijn dezelfde initiatiefnemers uit de vs actief. Analyses hebben de werkwijzeblootgelegd van deze mensen en hun financieringsstromen37. Zij beschrijven de connecties

tussen fondsen zoals de Heritage Foundation, American Enterprise Institute, Heartland Institute en George Marshal Institute en industriële organisaties, waaronder de olie- en de auto-industrie. Fondsen die een actieve rol speelden in het verspreiden van ontkenning van klimaatverandering. Het debat over roken en gezondheid heeft ook laten zien

dat deze fondsen en hun industriële sponsors bijzonder bekwaam zijn in het verspreiden van ontkenningen en het bespelen van de media met dezelfde methoden die je nu ook

ziet in het klimaatdebat, bijvoorbeeld door het inzetten van ‘ontkenningswetenschappers’die geen aantoonbare expertise hebben in de klimaatproblematiek38.'

Excuse me Bram. Zelfs Fred Singer heeft meer peer reviewed publicaties over klimaatprocessen op zijn naam dan jij (toon mij bewijs dat het niet zo is), zo'n tegen de politiek aanleunende herkauwer van andermans beweringen. Dan kan ik ook een hoogleraarstoel krijgen, als je dat deskundigheid durft te noemen. Wat welgevallige conclusies uit rapportjes shoppen kan ik ook zo, voor de helft van jouw tarief

Je inauguratie gaat dus eigenlijk over jezelf en die profdrir zegt me niks. Dat had Stapel ook voor zijn naam

Boels

Jij geeft het volgende aan

"Anti-klimaatalarmisten, zoals die zich hier manifesteren, vormen in die zin geen groep gezien de diversiteit aan achtergronden."

Op zich hoeven leden vaneen groep niet allemaal dezelfde achtergrond te hebben.

Essentieel is een doel en enige consensus over de vraag hoe dit doel te bereiken. ( wegen, middelen en ethiek)

Juist een diversiteit aan achtergronden kan een bijdrage zijn aan het oplossingsgericht denken. Je kunt elkaar vanuit verschillende disciplines aanvullen.

Essentieel is erkenning en waardering voor elkaars inbreng en consensus over het doel of de doelen

Je zou binnen deze groep b.v.een discussie kunnen opzetten met de vraag welke gemeenschappelijk(e) doel(en) binnen deze nagestreefd worden en hoever we willen gaan om die te bereiken.

@Hugo Matthijssen:

Mijn drijfveer en verontrusting betreft de feitelijke teloorgang van de geloofwaardigheid van delen van de wetenschap en het ontbreken van enig teken van verzet van de officiële wetenschappelijke wereld.

Het grote publiek verwacht van wetenschappers dat zij "nette" wetenschap bedrijven, wetenschap zonder vooringenomenheid en zonder binding met activistische groepen.

Het is toch van de gekke dat ik mij scheel moet lezen en soms blauw moet betalen om een beeld te krijgen van de vermeende consensus betreffende de klimaatproblematiek.

Niemand in dat klimaatwereldje laat een stem horen als (bijvoorbeeld) de Grote Meelifter Pier Vellinga weer aan het doordraaien is.

We moeten wetenschappers oproepen om zich niet voor een karretje te laten spannen en af te zien van de, in deze, valse collegialiteit.

Universiteiten en onderzoekinstellingen dienen zelf voorlichting te geven en geld daarvoor vrij te maken.

Het derde TV-net (NL3) is daar uitermate geschikt voor.

En dan niet door persvoorlichterij, maar door gekwalificeerde wetenschappers.

Wetenschap moet en wetenschappers moeten weer serieus genomen kunnen worden.

Boels Geheel eens.

De vraag is hoe dit te bestrijden.

Ik ben geen wetenschapper maar heb veel ervaring in drijfveren van mensen. Ooit actief als personeelsmanager van een provinciale milieudienst.

Vreemde zaken meegemaakt zoals een deskundige die de normen voor zware metalen in de grond vastlegde waarna na een jaar bleek dat de afgeplagde humus van een groot heideveld als chemisch afval naar de Vam getransporteerd zou moeten worden.

Nu de dagelijks praktijk:

Gisteren Vellinga op de tv wist te vertellen dat de zuidpool aan het smelten was en onderzoek dringend noodzakelijk. In werkelijkheid is het tegendeel waar.

Catrinus Jepma professor duuraamheid universiteit groningen heeft de enorme voordelen van windnenergie op zee afgelopen zaterdag gepromoot.

Er kan volgens hem in 2020 elektriciteit worden opgewekt voornamelijk met wind en aardgas als aanvulling.

Pagina groot artikel in de krant de redding voor het noorden.

kenniscentrum duurzaamheid en duizenden banen erbij.

Als je dan weet dat zijn achtergrond economie is en hij totaal geen zicht heeft op de techniek van energie opwekking zoals blijkt uit zijn stuk.

Wat je dus ziet is super ego's die via de media volkomen foute zaken de wereld ingooien en vervolgens alleen de eigen glorie in beeld hebben.

Zij zijn zo doorgeslagen dat ik eens een jurist heb horen roepen dat hij het beter wist dan die domme ingenieurs.

De praktijk.

Ik heb naar de krant uitgebreid gereageerd met links en mijn stukje wat ik had geschreven voor de ombudsman als reactie op de diarree van het ministerie inzake de voorlichting over windmolens.

Ik heb wel vaker gereageerd zoals op een artikel van een dorpshuisarts die koolzaad als middel zag om zijn dorp duurzaam te maken ( ook een halve pagina) eten koopt hij dan kennelijk in het naburige dorp.

Er volgt dan vaak geen enkele reactie en de materie is te ingewikkeld om in een ingezonden stuk van max 180 woorden te persen.

Een journalist vaart blind op b.v. deze deskundige professor.

Hoe te voorkomen?

Wetenschappers hebben nog steeds de cultuur dat je elkaar zoveel mogelijk respecteert en zij zullen elkaar dan ook niet snel aanvallen in de pers.

Het effect is dat figuren als Vellinga en Jepma met ondertekening van hun naam en geweldige titel de grootste onzin kunnen uitkramen.

Mijn voorstel is een denktank te vormen die elke week het meest onzinnige artikel in het nieuws letterlijk onderuit haalt maar dan op een zodanige manier dat de gemiddelde burger ook kan doorzien wat voor onzin er wordt uitgekraamd.

Er gaan nu miljoenen naar een expeditie voor onderzoek over de opwarming op de zuidpool.

Alleen dit filmpje geeft al aardig tegengas.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embed…

@Hugo Matthijssen:

Prima om speldeprikken uit te delen maar het behoort niet van ons te komen.

Het moet de intelligentia (waaronder de integere wetenschappers) toch ook opvallen dat er teveel figuren met een hoog zie-mij-eens-gehalte rondlopen en misbruik maken van de positie om wensdenken te propageren?

Het is eigenlijk helemaal niet zo moeilijk: de KNAW, als bewaker van de wetenschappelijke integriteit, verklaart de integriteitsrichtlijnen betreffende wetenschappelijk onderzoek ook van toepassing op publiekelijke "qualitata qua" uitlatingen van wetenschapsbeoefenaren.

Richtlijnen en gedragcodes werken echter niet zonder sancties; mogelijk moeten wetten aangepast worden.

Mr. Matthijssen,

Ik kan u alleen maar bijtreden:De integere wetenschapper heeft ook nood aan een integere media.

En daar wringt het schoentje wat.Door de vele fusies en budgetcuts zijn de redacties danig onderbezet geraakt. CTRL+C en CTRL+V zijn basisvaardigheden die iedereen beheerst, dus

een populair artikel aankopen is vast een pak goedkoper dan zelf onderzoek initieren.

Daar heb je immers geen dure, gespecialiseerde journalisten voor nodig die rustig de tijd nemen om één en ander uit te pluizen en nogmaals te controleren.

Het gevolg is dat media opnieuw erg vatbaar zijn voor verzuiling en liever tendensieus en anoniem berichten dan risico's nemen.De schellen zijn in 2008 van mijn ogen gevallen toen ik bijna alle Vlaamse kranten heb aangeschreven met het verhaal dat windboeren hier 21 turbines wilden inplanten op afstanden tussen 200 en 1200m van onze woningen. Op meer dan één vlak ongehoord. Ik dacht dat, als ik ze een initieel dossier zou overmaken met alle pro's en contra's mooi opgelijst (jaaropbrengsten, milieueffecten, waardevermindering, backupcapaciteit, …), er wel een journalist zou zijn die deze punten zou napluizen en er een onafhankelijk artikel over zou schrijven. Jongens toch, wat ben ik toen overal weggehoond. Iemand die zo'n romantisch beeld heeft over journalistiek,… wat een naieve looser!Ironsisch genoeg duiken er nu steeds meer kleine berichten op over het onderwerp met besluiten die ze al in 2008 hadden kunnen trekken. Onafhankelijk van mijn mening,… nu ja onafhankelijk: de windboeren-in-kwestie zijn 3 gewichtige politici die – geheel toevallig – ook zwaar op het bestuur van stroomdistributie, linkse kranten en de staatsomroep wegen. Ik zal wel wat last van agent detection hebben zeker.

Rik van der Ploeg (Universiteit Oxford, PvdA, oud staatssecretaris Cultuur/Media) was weer eens bij P&W (ook PvdA-honk). Het ging over de wereldranglijst omtrent de kwaliteit van universiteiten, gepubliceerd in Elsevier.

Feit: Nederlandse universiteiten komen niet voor op de eerste 30 plaatsen. We hebben een zesjescultuur. (PvdA genivelleerd!) Naast zeer nuttige aanbevelingen voor Nederlandse Universiteiten, maakte van der Ploeg verbaal een buiging voor KNAW voorzitter Robbert Dijkgraaf………

Het zette mij aan het denken: Wat is er aan de hand? Heeft de wetenschap in Nederland onder Dijkgraaf een stijging in kwaliteit doorgemaakt. Of heeft hij meer zichzelf gepromoot in DWDD (ook PvdA-honk!)?

We hebben in Dijkgraaf's KNAW-periode toch wel wat wetenschapsfraudes gehad (4 stuks), ook een PBL dat niet op de vingers werd getikt voor haar "slager keurt eigen vlees"-verder IPCC-evaluatie, een KNAW rapportconclusie over de staat van het klimaat, dat wetenschappelijk juist zeer zwaar op drijfzand staat, en feitelijk een schoffering is voor de traditie van de KNAW.

Dijkgraaf vertrekt na een "glansperiode" bij het KNAW voor de Nederlandse wetenschap naar Princeton.

Dijkgraaf is een gelauwerd wetenschapper, echter als KNAW-voorzitter heeft hij slechts onder de maat gepresteerd, voor een (politiek) onafhankelijke wetenschap, zo stel ik vast.

Gevolg van overvloedig PvdA-Groepsdenken in Nederland?

http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robbert_Dijkgraaf

Boels

kijk eens naar deze link

wij zijn saboteurs.

wil je je niet verdedigen tegen dit soort figuren?

let ook eens op tijd die de verschillende actoren het woord krijgen.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-uKIn1X10cc&fe…

DaVince

Er komt een tijd dat de wal het schip zal keren.

Wij hebben een nationale ombudsman die heeft ons ministerie aangesproken op hun foutieve voorlichting wat in de praktijk ook geen enkel effect blijkt te hebben

Leerzaam verhaal; als een spiegel die uitnodigt tot de vraag: kan ik mijzelf recht in de ogen kijken? Het is verleidelijk om je te verstoppen in de bescherming van de school vissen. Streven naar (zelf)kritiek, grondigheid en vermijden selectief informatie te kiezen is lastiger dan het lijkt. Maar het verhoogt wel de geloofwaardigheid van de groep als geheel en de status van het gedachtegoed. Groepsdenken doorbreek je niet met pure rationalieteit; een forse dosis inleving en luisteren levert veel meer op; ook dit is lastiger dan het lijkt. De winst is echter aanzienlijk.

@Jeroen

Zo'n spiegel blijft moeilijk.

Ik vind zelf de sceptici een kruiwagen met kikkers, allemaal stront-eigenwijze eigenheimers die heel snel de neiging hebben om ergens tegen in te gaan, of het nu door een alarmist of een mede-scepticus gezegd wordt.

Na tien jaar overweldigende media-indoctrinatie zijn de paar resterende sceptici uiteraard van nature recalcitrant. Op onze bijeenkomsten zijn we dan ook lekker fel en die eindigen vaak met rode oortjes!

Het voelt dan ook niet als een geïsoleerde groep zoals hierboven beschreven. De kenmerken daarvan zijn m.i. exact toepasbaar op de leden van het Hockey-team, en eigenlijk helemaal niet op de groep Nederlandse sceptici.

Maar goed, er zitten vast bij ons ook van die typische groepsdenk-symptomen. Vandaar mijn vraag om voorbeelden te noemen.

Ik vind zelf de nadruk op de stabilisering van de temperatuur na 1998 een voorbeeld, en überhaupt de nadruk op temperatuurreeksen.

Die zegt toch niets? Als hij wel wat zegt, dan zegt de stijging daarvoor ook wat. Ook de meeste alarmisten ontkennen niet dat er andere invloeden zijn, alleen dat de achterliggende trend stijgend is.

De uiteindelijke temperatuurreeks bewijst dus nooit iets, voor geen van beide partijen. Toch wordt de stabilisatie bijna standaard door sceptici gebruikt als vernietigend wapen tegen alarmistische claims.

Maar meer kan ik niet bedenken.

En er wordt hier ook weinig aangedragen dat tot ernstige bezinning maant…

Dus zal het wel meevallen met de groupthink van ons clubje!

De fixatie op een gemiddelde temperatuur hebben zowel (door de bank genomen) alarmisten als sceptici gemeen.

(Of de sceptici worden er toe gedwongen omdat alarmisten er mee schermen)

Een onzinnige maatstaf als je bedenkt dat gelijktijdig arctische temperaturen in de tropen en tropische temperaturen in de artica's geen invloed op het gemiddelde hoeven te hebben.

Groepsdruk, daar is het klimaat niet tegen bestand……

Frans, je bedoeld hoge druk of lage druk? Dan hebben we het weer over het weer!

Climategate.nl refereert vooral naar de klimaat-hoax die door alarmistisch gepolitiseerd groepsdenken vooral aan de linkerkant van het politiek spectrum wordt in leven gehouden en met gesubsidieerde en aanhoudende propaganda wordt versterkt.

Beste Turris, Mijn opmerking is uiteraard ironisch bedoeld en verwijst inderdaad naar het linkse groepsdenken over het klimaat (de klimaat-hoax)en de druk vanuit die groep om zo te denken (anders hoor je er niet meer bij of krijg je geen subsidie meer).

Het stuk over groepsdenken, afkomstig van het werk van Irving Janis, heb ik naar Theo Wolters gestuurd omdat me regelmatig is opgevallen dat sceptici de ondoordringbaarheid van alarmisten aan alarmisten toeschrijven. Daarmee plaatsen de sceptici zichzelf buiten het probleem, wat een bekend symptoom van groepsdenken of tunnelvisie is. Hoe zeer ik me ook kan vinden in veel overwegingen van 'ons' skeptici, toch zie ik nooit een poging om de ondoordringbaarheid van de alarmisten te doordringen. En dat is heel vreemd want de alarmisten zijn heel eenvoudig een 'operationally closed system' (Francisco Varela), dus best bereikbaar, maar alleen op de juiste manier. Misschien helpt mijn artikel over geloofsvermogen dat Theo in zijn stuk genoemd heeft, maar waarop ik nog van niemand een reactie heb ontvangen. Helemaal voorspelbaar: mensen lezen alleen iets van een onbekende als iemand anders hun dat nadrukkelijk aanraadt, mits zij die iemand anders goed kennen en belangrijk genoeg vinden.

Arnold, je lijkt een punt te hebben met je bereikbaarheid.

AGW-alarmisten zijn weliswaar bereikbaar, niet vatbaar. In discussies loop je vast, bots je op een muur, bereik je geen afstemming. YvdB, NN en andere gefrustreerde AGW-bloggers op climategate.nl zijn daar treffende voorbeelden van.

Ik vergelijk het AGW-klimaat-alarmistische wereldsysteem met de Katholiek Kerk (vergelijk : de AGW-gemeenschap), met de Paus (vergelijk: Al Gore), de Curie (vergelijk: het IPCC), de Inquisitie (vergelijk: GreenPeace) en de gelovigen ( vergelijk : de groen & linkse stemmers).

Het AGW-systeem is tot op heden impermeabel, met hun diep religieuze gelovigen valt soms redelijk een eind te discussiëren, echter in discussies kom je toch steevast terecht in hun cirkelredeneringen.

@Arnold:

Wat mij beteft heeft het niet te maken met de ondoordringbaarheid van alarmisten, maar met aplomb waarmee betwistbare resultaten als bewijs worden gepresenteerd.

1. een gemiddelde globale temperatuur om de aard/verandering van het eenheidsklimaat te duiden is fysische en rekenkundige onzin.

2. de lef om lineaire trends te publiceren van een niet-lineair systeem met onzekerheden in de milli-Kelvin is stuitend.

3. de correlatie tussen het CO2-gehalte en de temperatuur is nul,niks.

4. met verkeerd toegepaste statistiek is van alles aan te tonen.

@Arnold

"De alarmisten" is in dit verband een te generaliserend begrip. De AGW aanhangers die zich mede vanuit hun functie in het debat mengen zijn – publiek – uiteraard nooit bereid tot enige concessie.

Maar veel wetenschappers die soms (haast argeloos lijkt het wel) de AGW hypothese accepteren, blijken op hun eigen vakgebied en in persoonlijke gesprekken veel genuanceerder en flexibeler te denken dan je zou verwachten.

Met hen is best te praten, zolang je je maar niet fanatiek achter de sceptische clichés verschuilt.

Met alarmisten bedoelen we Milieu Defensie, Natuur & Milieu, Vroege Vogels, GreenPeace, Wouter van Dieren, het KNMI van voor 2007, Robert Dijkgraaf, Pavel Kabat, Al Gore, IPCC, PBL, Wubbo Ockels, Jacqueline Cramer, Lucas Reinders, Pier Vellinga, Cees Veerman, Wijnand Duyvendak, Diederik Samsom. Elsevier heeft een speciale editie uitgegeven over deze alarmisten.

Zij vormen het AGW-defensie-systeem: Het AGW-systeem is tot op heden impermeabel, met hun diep religieuze gelovigen valt soms redelijk een eind te discussiëren, echter in discussies kom je toch steevast terecht in hun cirkelredeneringen.

In het debat Hans Labohm/Jan Paul van Soest geeft van Soest heel eenvoudig en begrijpelijk weer hoe het komt dat wij de aarde aan het opwarmen zijn. CO2 belet de afvoer van warmte. Op dat moment krijgt of neemt Hans niet de gelegenheid om met heldere argumenten van Soest tegen te spreken. Jammer!

Wat is de kennisbron van van Soest? Wat heeft hij zelf gestudeerd, weet hij meer dan bijv. Vellinga.

Hans Erren schrijft op 15 januari in deze reeks:

Ik ben regelmatig bezig met skeptici te corrigeren over de CO2-cyclus en infraroodfysica. Zoals daar zijn Hans Jelbring, wijlen Ernst-Georg Beck, Hans Labohm en Arthur Rorsch, en ook op dit blog meen ik dat ik niet alles voor zoete koek slik wat mijn medebloggers presenteren.

Mij lijkt het gewenst dat klimaatsceptici het eens worden over wat Hans Erren naar voren brengt. Dat hoeft niet tot groepsdenken te leiden. Wel fijn als er een actuele echte molecuulfysicawetenschapper aan deelneemt.

Volgens mij geeft Labohm ook duidelijk weer, dat de opwarming van de aarde met als primaire oorzaak CO2-uitstoot door het IPCC en door alarmistische klimaatwetenschappers sterk wordt overdreven, bij gebrek aan sluitend bewijs.