Na de euforie van het klimaatakkoord van Parijs (2015), waarin landen de wens hebben uitgesproken om de opwarming van de aarde (eigenlijk: atmosfeer) te beperken tot 2 graden Celsius, en liefst 1,5 graad, hebben zich enkele belangrijke ontwikkelingen voorgedaan in de internationale klimaatdiplomatie.

Zoals ik al eerder schreef was deze euforie misplaatst, al was het alleen maar omdat men het eens was geworden over niet meer dan een verzameling intentieverklaringen inzake het klimaatbeleid van de individuele deelnemers, waaraan geen sancties waren verbonden bij niet–nakoming. Bovendien was de som van hun beloften bij lange na niet voldoende om de gestelde doelstellingen te halen, ook al omdat grote CO2–emittenten als China en India tot 2030 waren vrijgesteld van enige verplichting, of zelfs belofte om hun CO2–uitstoot te beperken.

Onder de titel, ‘Bolsonaro in, Merkel out: the Paris climate gang is breaking up’, schreef Sara Stefanini voor Climate Home News een overzicht van de scheuren die zich thans manifesteren in de coalitie van landen die destijds een voortrekkersrol speelden in het internationale klimaatbeleid.

Ik pik er een aantal elementen uit.

In 2015, a group of countries banded together to shape the global climate pact, but political turmoil is pulling the alliance apart. …

In 2015, the world’s top two emitters, the US and China, joined with Brazil, some small island countries and the European Union, led by Germany, France and the UK, to land the agreement.

But climate change politics have shifted significantly since then, with two more big tilts this week. Brazil elected a staunch and radical anti–environmentalist president, while Germany’s Angela Merkel confirmed her exit plans, further weakening an already fading image as the “climate chancellor” and Europe’s go–to leader in the field.

It is the latest bout of a malaise that has infected climate efforts since Donald Trump was elected in the US in 2016.

Now, in many important countries, climate scepticism and economic nationalism are usurping the international green enthusiasm of 2015. As a result, political support for slashing greenhouse gas emissions, sending aid to the poorest and most vulnerable countries and discussing it all in multilateral summits is waning. Others that remain committed to climate action are consumed by domestic concerns – like Brexit in the UK, and political instability in Germany.

None of this bodes well for the Cop24 climate summit in Katowice, Poland this December, where nearly 200 countries must agree the complex rules to keep each other on track to fulfil the Paris goals for limiting the temperature rise. Negotiations in the run-up to what observers are calling the most important Cop since Paris have been slow and fraught. …

The election of the rightwing Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil is set to bring radical changes, including opening the Amazon to mining, agriculture and construction and merging the environment and agriculture ministries. Bolsonaro said last week that he would not pull out of the Paris Agreement, as long as it did not affect Brazilian control over the Andes mountains, Amazon and Atlantic Ocean. Previously, however, he praised US president Trump for his decision to withdraw. …

Compared to Bolsonaro’s Brazil, the German shift will be far more subtle – with continued headline support for the Paris Agreement and strict rules to fulfil it, as well as financial aid for poorer countries.

But Merkel’s announcement on Monday, that she will step down as leader of her conservative Christian Democratic Union and will not stand for re–election in 2021, further weakens her clout. Her image on climate change has already taken a hit this year, amid criticism for allowing deforestation for a coal mine, failure to meet the country’s 2020 emissions reduction goal, and slow progress on setting an end date for coal use.

It marks a change from 2015, when Merkel won praise for securing a G7 commitment to keeping the temperature below 2C, just months before Paris. Germany’s Energiewende pivot to renewable energy has also lost its lustre since then, and is now blamed for keeping coal afloat to make up for the shutdown of emissions–free nuclear power plants. …

Meanwhile Australia – always reluctant to take climate action that might harm its large resource economy – is growing more brazen, criticising international climate talks and funding and ruling out a quick end to coal use. …

Similar views are still alive and kicking in coal–reliant Poland, which presides over Cop24. Warsaw tends to stress the need for a gradual transition from coal, along with forestry and technology to catch CO2 and offset fossil fuel burning, and the rise of electric transport – which could present new demand for coal-fired power.

Even China, which has set high targets for cutting coal use and adding renewables and electric vehicles, sticks to a hard line behind negotiating doors. It wants to differentiate the responsibilities for developing economies and put more burden on developed countries – something the US and EU oppose. …

Bron hier.

En zo zijgt het kaartenhuis van het internationale klimaatbeleid langzaam ineen.

Maar er is nog één klein landje in het noordwesten van Europa, dat zich met zijn energietransitie dapper verzet tegen deze massale erosie van internationale steun voor het klimaatbeleid en – zonder zich daarvan ook maar iets aan te trekken – in zijn eentje de wereld wil redden van die catastrofale opwarming (die overigens maar steeds niet wil komen).

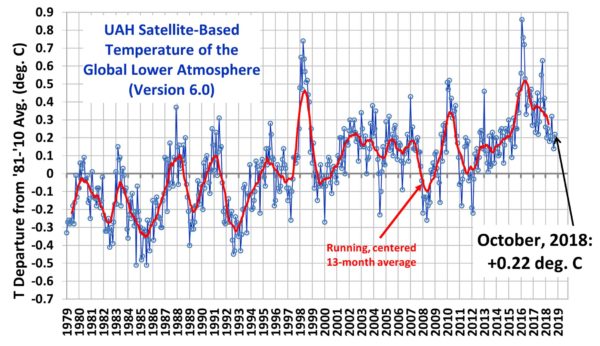

Voor recente satellietmetingen van de gemiddelde wereldtemperatuur zie hier:

Eventjes factchecken:

“But climate change politics have shifted significantly since then […] Germany’s Angela Merkel confirmed her exit plans”

Wanneer heeft Merkel ooit beweerd dat zij volledig afstand wil doen van de Parijs-akkoorden?

Merkel is geen voorstander om nieuwe, strengere Europese doelstellingen te formuleren. Ze stelt vast dat er lidstaten zijn die momenteel moeite hebben om de huidige doelstellingen te halen, en oordeelt daarom dat het niet constructief zou zijn om de lat nu plots nog hoger te leggen.

Ze blijft wel degelijk een voorstander van de bestaande EU doelstellingen.

“Ze stelt vast dat er lidstaten zijn die momenteel moeite hebben om de huidige doelstellingen te halen ..”

Waarmee ze feitelijk bevestigt dat de Energiewende van de BRD een flop is.

Eventjes factchecken:

“Wanneer heeft Merkel ooit beweerd dat zij volledig afstand wil doen van de Parijs-akkoorden?”

Wie beweerd dat zij dat beweerd?

Dat is een insinuatie van jouw kant, waarschijnlijk veroorzaakt door jouw onvermogen om begrijpend Engels te kunnen lezen.

En in het recente verleden heb je ook al meermaals blijk gegeven dat Nederlands ook niet je sterkste punt is.

Niet best voor een “wetenschapper”.

Eh. Nederlands? Spellen enzo?

Wie beweerD dat ze beweerD?

Dat noem ik een Klavertje doen. Je weet wel, iemand de les lezen en dan op 14 ipv

140 miljard uitkomen maar dan met taal.

@Henk dJ

Niet zo vooringenomen lezen. Exit plans van Merkel betreffen haar exit uit de politiek.

Je kunt het eigenlijk op twee manieren lezen. Haar aankondiging van exit uit de politiek heeft niets te maken met het klimaatbeleid. Dus, waarom wordt dat er dan bij gehaald? Om toch maar iets te kunnen insinueren, veronderstel ik. Want zo werkt het: je gooit wat ongerelateerde zaken samen in één artikel, en de vooringenomen lezer trapt in de val van de insinuaties. En het populisme van het AGW-negationisme kan zo weer verder gaan!

Tjezis Henk, lezen is niet makkelijk, moeilijk doen gaat je beter af…

Er staat ‘Bolsonaro in, Merkel out’ in de titel, in en out gaan dus over politiek niet over het akkoord van Parijs.

Moeilijk hè, lezen! Merkel’s exit plans gaan over het feit dat ze heeft besloten geen bondskanselier meer te willen zijn.

Wat een mooi stroman heb je weer gefabriceerd, Henk dj! Fijn, met vette letters. Misschien dat je volgende keer beter eerst even kunt doorlezen, bijvoorbeeld dit artikel: http://www.climatechangenews.com/2018/10/24/brexit-germany-erode-eu-climate-resolve/ of deze: http://www.climatechangenews.com/2018/06/12/germany-miss-2020-climate-target-government-concedes-official-report/

Je moet wel duidelijk lezen natuurlijk, Tije! Je eerste link is perfect in overeenstemming met wat ik schreef: “Merkel is geen voorstander om nieuwe, strengere Europese doelstellingen te formuleren.” En het tweede artikel is in overeenstemming met wat ik schreef: “dat er lidstaten zijn die momenteel moeite hebben om de huidige doelstellingen te halen”

Dus niets “stroman”

Nee Henk dj, jij haalt weer eens het een aan, om het ander te kunnen beweren. Er staat duidelijk geformuleerd dat Merkel niet van plan is de doelen te gaan halen. Jij maakt daarvan dat Merkel Parijs volledig zou verlaten. Dat is nu een stroman maken van andermans formulering, Henk dj.

@Tije Hdj is bedreven in betekenissen iets te verdraaien of mensen woorden in de mond te leggen of gewoon te bluffen.

“Er staat duidelijk geformuleerd dat Merkel niet van plan is de doelen te gaan halen”

Nee, dat staat er niet “duidelijk”. Er staat bijvoorbeeld wel “failure to meet the country’s 2020 emissions reduction goal”. En er staat ook dat “Others that remain committed to climate action are consumed by domestic concerns”, dus dat zij ook andere kopzorgen heeft. Maar dat alles betekent dus niet dat dit haar “plan” was. Kijk dus even in de spiegel, en je zult merken dat je zelf een stroman hebt…

@ Tije: Hetzler is bedreven in beweringen te maken die hij dan nooit kan aantonen, maar dan te bluffen dat hij ze ooit wel eens heeft aangetoond. Zo heb ik hem al zeker 15x gevraagd voor een onderbouwing dat AGW een “weerlegd sprookje” zou zijn, maar hij negeert dat telkens weer. weerleg

OF de vaststelling dat de overgrote meerderheid van de klimaatwetenschappers AGW erkennen en oordelen dat hier aktie rond dient te worden genomen: ook dat trekt hij in twijfel zonder ooit maar enige motivatie hiervoor te geven.

Of al de fouten in zijn “berekening” van de kosten van de energietransitie. Ook daar wil hij maar niet op reageren.

Je zou haast de indruk gaan krijgen dat het accoord van Parijs precies het tegenovergestelde veroorzaakt van wat was beoogd. Het was gebaseerd op de welwillendheid van de landen . Maar Obama werd vervangen door Trump en in Brazilië verloor de de socialistische kandidaat van een gevaarlijke rechtse gek . ( omdat ze zelf ook gecorrumpeerd waren )

Over hele wereld wordt de ruk naar rechts zichtbaarder, met deze gevaarlijke gek in Brazilië als laatste hoogtepunt . Actie = reactie.

Deze Bolsenaro is exponent van de heersende klasse volgens een nog 19 de eeuws -feodaal- model, gecombineerd met een rigide macho – cultuur. Zoals ook in het artikel beschreven zullen zij de bedrijven die het land komen plunderen voor de productie van biodiesel ethanol, methanol en andere derivaten van natuurlijke bronnen; om fossiele brandstoffen te vervangen, geen strobreed in de weg leggen. ” Het kan verkeren ” .

Bert Pijnse van der Aa

Ook hier geldt weer “Wie wind zaait zal storm oogsten.

Als je te lang blijft wegkijken en hoofdzakelijk politiek correcte praatjes verkoopt, krijg je op termijn je trekken thuis.

Met elkaar in gesprek blijven op een inhoudelijke manier en met oog voor de belangen/wensen van anderen zal de oplossing van problemen mogelijk dichterbij brengen. Mogelijk kan een stapje richting kernenergie die rol spelen. De een minder CO2, de ander een minder volatiel energiesysteem.

Hr van Beurden , bij u krijg ik altijd het idee van iemand die net zo lang zou praten, totdat de Eerste en Tweede wet van de thermodynamica, inclusief de zwaartekracht- wet zijn weggepoldert . Ofwel het probleem ontkennen en vervangen door een virtuele waarheid ( dat windmolens stroom leveren 24/7 ) “slechte heelmeesters maken stinkende wonden ” .

De geschiedenis een opeenvolging van hoogte – en dieptepunten en leert ons dat alleen radicale gebeurtenissen voor veranderingen zorgden. Pappen en nat houden voedt dat systeem, totdat het uit elkaar spat .

Ik schat dat u schoolmeester of leraar bent/was .

.bert..ik ben t helemaal met je eens…ik sla tegenwoordig peter ook over…mvg…bart.

bart

Laat ik daar nu niet mee zitten. Grappenmakers kunnen niet zo veel met nuances. Véél te saai en niet brandbaar genoeg.

Peter,

er zal subsidie bij een kerncentrale moeten, en het duurt heel erg lang. JE conformeren aan de werkelijkheid is niet het verkopen van politiek correcte praatjes, het affakkelen van mensen die is sprookjes geloven (zoals “sceptici”) is een inhoudelijk gesprek aangaan.

Als je onzin verkoopt dan vertel ik je dat, als je vind dat ik niet aardig ben moet je jezelf beter informeren en geen onzin verkopen.

Dat kan de discussie op gang brengen.

Het herhalen van steeds dezelfde onzin is wat de inhoudelijke discussie blokkeerd, en hoe sta jij in dit verhaal? Als het moeilijk wordt geloof je mensen die je het op een voor jouw begrijpelijke wijze uitleggen, maar je weigert te controleren of de voor jouw begrijpelijke wijze ook maar enigszins onderbouwd wordt door de natuurwetenschap, want daar heb je geen verstand van. of dit standpunt afwijkt van de natuurwetenschap maakt voor jou niet uit.

Mensen die geloven in de platte aarde hebben ook logisch klinkende argumenten, dat maakt hun positie nog niet waar of ook maar enigszins interessant om mee te nemen in een volwassen discussie.

Dus in het vervolg probeer eens te vragen naar een wetenschappelijke onderbouwing van een standpunt inplaats van onzin van anderen te herhalen

Alle energieproducenten zijn geborgd door de Staat, dat wil zeggen dat de Staat financieel ingrijpt als de energieproductie de maatschappelijke belangen zouden gaan schaden.

Hetzelfde zou moeten gaan gelden voor kernenergie.

Echter er wordt wat bij verzonnen, nl. de waarborg dat de kernenergieproducent ook moet opdraaien voor de eventuele maatschappelijke schade.

Dat is nogal dubbel want ik heb groen nooit gehoord het verhalen van de schade die men zelf toekent aan fossiel.

En dat komt omdat de fossiele producenten het afkopen door “hernieuwbaar” voor een stukkie te omarmen.

De groen gedachte is niet meer dan: bevredig mij, dan zal ik niet bijten.

Klimaatprostitutie.

@Boels klopt. De kernenergiewereld heeft een onderling verzekeringsfond voor calamiteiten

@Bert Pijnse van der Aa 7 november 2018 om 09:59

“Deze Bolsenaro is exponent van de heersende klasse volgens een nog 19 de eeuws -feodaal- model, gecombineerd met een rigide macho – cultuur.”

Ik zie geen wezenlijk verschil met de huidige NL-politiek; het geweld is verpakt in cadeaupapier met een lintje,

– 10 jaar lang procederen om asiel te mogen krijgen; wie begrijpt nu zoiets.

– ondanks de sociale woningnood wordt er geen spade meer in de grond gestoken; wie begrijpt zoiets.

– defensie krijgt gebroken geweertjes; wie begrijpt zoiets.

– NGO’s worden gesubsidieerd en mogen langs ondemocratische weg meepraten; wie begrijpt zoiets.

– “nette oplichters” worden niet vervolgd, wie begrijpt zoiets.

– afgeserveerde politici duiken op als voortrekkers van beleid; wie begrijpt zoiets.

– ..

Boels claimt onderwijs gekregen te hebben, wie begrijpt nu zo iets

Hij weet in ieder geval foutloos te schrijven.

@Janos:

Is groene terreur voor jou iets duidelijker?

Nee

Leg het eens uit ?

De enige terreur komt van de ontkenners die weigeren zich open te stellen voor wetenschappelijk onderbouwde argumenten

Dat noem ik terreur een samenleving gijzelen door steeds weer de doelpalen te verschuiven en alle onderbouwing categorisch af te wijzen

Bert Pijnse van der Aa

Los van het feit dat ik er geen enkel probleem mee heb dat ik inderdaad leraar was, heb ik toch enkele vragen.

Zie je kernenergie als een bruikbare optie?

Vind je het beter dat windmolens hun volatiele energie aan het net blijven leveren?

Kun je de windmolens die er al zijn of op stapel staan niet beter waterstof laten maken en dat toevoegen aan Russisch gas en het gasnet in takt laten?

Ik bedoelde allerminst te zeggen dat ik een fan ben van windmolens, maar om ze stil te zetten nu ze er staan lijkt me ook ongewenst. Dan liever waterstof maken totdat ze versleten zijn en het ook kan met kernenergie. Biobrandstof van bruikbaar hout of voedselgewassen lijkt me een slechtere oplossing dan waterstof.

Polderen en met elkaar in gesprek blijven vind ik beter dan elkaar verketteren.

Maar de 1e en 2e wet op de thermodynamica en de zwaartekracht wil ik allerminst wegpolderen. Ik ben er van doordrongen dat zoiets niet gaat lukken.

Toch die bestaande molens maar liever stilzetten en zo snel mogelijk slopen. De opbrengst is verwaarloosbaar, het zicht is afgrijselijk en van onderhoud en reparatie ben je dan ook af. De vogels zullen er blij mee zijn.

Gert Visser

Ik zeg niet bij voorbaat nee op dat stilzetten. Ook ik zag liever dat men zich eerst had bedacht en die molens er niet waren gekomen. Maar ze zijn er, een groot deel van de kosten zijn gemaakt. Als ik een keuze moet maken, dan zeg ik: Geen windmolens erbij op land, de rest van het net af en die waterstof laten produceren voor een waterstofeconomie als aanvulling op kernenergie tot dat eventueel toereikend is om die waterstofproductie over te nemen.

Peter,

en vervolgens aardgas maken uit CO2 en de waterstof.

Erik

En dan maar hopen dat het kostendekkend kan. Altijd beter dan houtgas maken uit bruikbaar hout. Beter kan het met afgevangen CO2 uit de verbrandingsoven.

Misschien is een waterstof economie zo gek nog niet. Zeewater genoeg. Waterstof > Methaan > Electriciteit. Dat meer dan genoeg kun je van Lithium niet zeggen. Bovendien vind ik het nogal dwaas om een zwaar accupakket overal mee naar toe te slepen. Doet me denken aan een zeeschildpad, bijna net zo prehistorisch.

En weer een dolkomische reactie van dhr. van der Heijden tot slot, waarbij men de vraag kan stellen, wat deze heer nu eigenlijk onder onderwijs verstaat. Weer heel grappig die activistenhumor.

Yes, er kan afscheid genomen worden van vele politiek ideologisch verdwaalden. Zo werd gevraagd aan Jesse Klaver / GroenLinks of hij / zij “climate control deniers” waren, omdat ze kernenergie nog steeds afwezen.

Faiza Oulahsen van Greenpeace Nederland beweert op twitter dat Lubach het “niet goed heeft begrepen over kernenergie !” :-) ; Dan ga je wel af als GreenPeace!

Ook op de StaatsRadio1 mocht GreenPeace vanochtend ook ageren tegen de relatief goedkope veilige kernenergie voor Nederland.

Zo zou volgens GreenPeace de (“gratis”) duurzame energie (windturbines en zonnepanelen) nu geheel zonder subsidie kunnen en kunnen we kernenergie uit Frankrijk kopen (dat laatste is waar!).

Dat de consument opgezadeld wordt met 800 ~ 1000 miljard € “duurzame” transitiekosten door de Nijpolitaanse klimaattafels van RutteIII-klimaatbeleid, dat wordt door GreenPeace immer verzwegen.

Dat deze ideologische vervormers van harde feiten (GreenPeace) een podium krijgen, zonder dat door de journaille er weerwoord wordt gezocht bij critici, dat moet afgelopen zijn!

Waarbij natuurlijk wel vastgesteld moet worden dat de 1000 miljard een duimzuigseltje is van Scheffer zonder enige onderbouwing

Maar het bevestigd zijn opinie dus is het waar !

Zo eindelijk weer eens goed nieuws, einde oefening.

Nederland nog een kwestie van tijd.

Net als Rutte zijn vertrek, rustig afwachten.

Zo als ik al eerder zei, al is de leugen nog zo snel de waarheid achterhaalt hem wel!

Maar voorlopig wordt onze portemonnee leeg getrokken voor helemaal niets.

Kijk hoe absurd dit hele klimaathysterie is:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NxQSubDqlBE

1000 miljard € dus volgens CE Delft komende 20 jaar. 50 miljard per jaar energie transitie kosten voor de burgers.

Nee Scheffer ,

Niet weer die leugen herhalen.

Dit is natuurlijk die. Excuses.

Als ik het zou mogen zeggen zou ik de komende 30 jaar gas stoken en alle flauwe kul met wind, zon, electrische auto’s en warmtepompen vergeten. Om intussen een gedeelte van de uitgespaarde miljarden te besteden aan samenwerking in de ontwikkeling van een inherent veilige, afvalarme, massaproduceerbare goedkope kernsplitsingcentrale waar de wijdere wereld ook wat aan heeft. In te voeren vanaf 2050.

Het zal er wel van komen, maar eerst moet nog veel tijd verspild en heel veel geld over de balk.

Bjorn Lomborg, TV interview with France24

The 2015 Paris climate agreement is a highly costly treaty that will change little. That’s the view of Bjorn Lomborg, who’s been named one of the most influential people of the 21st century. Lomborg, who has his own think tank and has written several books on the issue, admits that climate change is real, but says the Paris accord is a tiny way of doing something about global warming. He argues that it will solve just one percent of the problem at a very high cost.

De evaluatie is in 2023 afgesproken niet? Vroeg genoeg als je in 2015 met zoiets dergelijks van start gaat. Of we die 1.5 graden halen hangt niet alleen af van de uitstoot maar ook van de aanname’s die je doet qua klimaatgevoeligheid en de mate waarin de Aarde die CO2 kan verwerken. De uitstoot is niet wat de opwarming veroorzaakt maar het stijgen van de concentratie. Indien we schattingen der sceptici aanhouden zal het met gemak onder de 1,5 graden blijven en sommigen geloven zelfs nog steeds dat de ijstijd in 2019 gaat aanbreken. Wat betreft de CO2 concentratie, die ontwikkeling is voorlopig erg gunstig. Het lijkt er op dat we de komenden jaren zelfs onder RCP2.6 blijven. Misschien wel de reden waarom het niet zo hard opwarmt.

Hermie, zij geloofd in die kleine ijstijd.

PROFESSOR VALENTINA ZHARKOVA

Zharkova was een van de weinigen die correct voorspelde dat zonnecyclus 24 zwakker zou zijn dan cyclus 23 – slechts 2 van de 150 modellen voorspelden dit.

Haar modellen hebben een nauwkeurigheid van 93% en haar bevindingen suggereren dat een Super Grand Solar Minimaal op de kaart staat vanaf 2020 en dat het 350 – 400 jaar duurt.

Max, De zon wordt zwakker, en zwakker en zwakker en zwakker. Misschien nog een reden dat de opwarming wat geringer is dan verwacht. Maar als met het verstrijken van de jaren het maar niet wil afkoelen ondanks die zwakker, en zwakker en zwakker en nog veel zwakker wordende de zon, wat moeten we dan concluderen?

Hermie, ja ik weet het, maar ik zie wel steeds meer berichten hierover verschijnen, we zullen zien, het is trouwens niet te hopen, dan hebben we nog een groter probleem.

Max, Ja, het is te hopen dat CO2 wel een opwarmend effect heeft want als dat niet zo is dan valt onze regelknop voor de toekomst weg. Een kleine ijstijd zit niemand op te wachten. Een echt groot probleem hoeft het overigens niet te zijn. Nederland kende zelfs een gouden eeuw tijdens minder warmere tijden.

Hermie

Geef je deze verklaring een kans?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M_yqIj38UmY

Typisch een CG Pavlovstuk over ‘Parijs’ met een verwijzing naar Bolsonaro, de nieuwe regeringsleider van Brazilië, zonder enige inhoud of beschrijving van de energieproblemen: corruptie met Petrobas, stakingen in de rtansportsector, problemen met privatisering, hydro-energie projecten in de Amazone enz. enz.

Het gaat zoals de oprechte CG christenmensen betaamd gelijk ‘vol op het orgel’…als er maar teugen! de renewables en het terugbrengen van de CO2 uitstoot uit volle borst gezongen kan worden.

Misschien dat Hans zich tegelijkertijd eens zou kunnen inspannen om althans enige context aan te geven van een op zich erg complexe sociaal economische situatie waarin het land verkeerd mede door de stijgende prijzen van fossiele brandstoffen.

Maar goed even voor de goede orde tenminste enige info over Bolsonaro en zijn energiebeleid.

Op de ‘vertaler’ ziet het er zo uit.

https://www.ambienteenergia.com.br/index.php/2018/10/15-promessas-de-jair-bolsonaro-para-area-de-energia/35072

Het zou deze site sieren als de milieu/energie/klimaat skoop eens wat breder zou liggen

Zoals Pijnse aangeeft is Brazilië nu juist het land waar ze de ‘biofuels’ hebben uitgevonden en er zelfs al lang voor Grienpies de voordelen van inzagen!

Of hebben ze het dat wat dat betreft misschien wel niet bij het juiste eind? Moeilijke en complexe wereld hoor die energiewereld.

Deze site moet niet al te simplistisch worden, of het nou over kernenergie of biofuels gaat, daar schiet niemand wat mee op.

d’ Ólivat : Max 7 november 2018 om 14:00, voor u, geeft het antwoord op uw latere reactie. Brazilië heeft 80% van haar Savannes gekapt en is nu haar Amazone jungle bezig te slopen voor biomassa / biofuels. Weinig respect voor uw analyse dus.

Bjorn Lomborg, TV interview:

Global warming: ‘Paris agreement will leave 99% of the problem unsolved’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4UhbUNMQgc

Gerard,

Je schrijft: ‘Deze site moet niet al te simplistisch worden, of het nou over kernenergie of biofuels gaat, daar schiet niemand wat mee op.’

Zeker!

Doe er wat aan!

Veel mensen waren na de grote party in Parijs in 2015 losgekomen van de grond. Nu eindelijk na 3 jaar de facturen van het feest worden ontvangen, ontstaat mogelijk een omgekeerde beweging. Klimaatbeleid is vooral ook economie. Alle prachtige, dure, groene en inefficiente plannetjes en speeltjes moeten uiteindelijk ook betaald worden.

Ook de huisfilosoof van Klimaatverandering.nl, Goff Smeets is weer geland op aarde en is helemaal klaar met oplossingen en legt zelfs het IPCC over de knie.

Kwootjes:

“IPCC laat na om loud and clear te vermelden dat we te maken met een super wicked problem (!) En dat voor dergelijk probleem gewoon geen oplossing te bedenken of te calculeren is”.

En:

“Ik ga een stap verder en zie klimaatverandering niet als een op te lossen probleem maar als de realiteit hier & nu waarmee en waarin we moeten zien te leven”.

Sorry, ik kan het allemaal niet meer volgen hoor .

Vragen :

Zijn de mensen alhier nu blij met de uitverkiezeing van deze Bolsenaro, waarbij vergeleken Trump een koorknaap is , of vinden ze het wel een fijne vent .

2 ) vinden mensen alhier nu, dat het vervangen van fossiele brandstoffen, zoals voorgestaan door de aanhangers van de energietransitie , door biofuels en er voor allerlei processen ( productie van mierenzuur en bioplastics ) – opnieuw – derivaten van natuurlijke bronnen worden ingezet ? 3 ) dat daarbij de situatie zou ontstaan dat aanhangers van de energietransitie handjeklap doen met deze bolle se nario ?

In zijn boek ” de tovenaar en de Profeet ‘ verbindt Charles C. Mann de profeet met de natuurbeschermer ( William Vogt ) en de ’tovenaar’ met de technoloog ( Borlaugh ). Hoor ik nu bij de Tovenaars club of die van de profeten .

@Bert Pijnse van der Aa 7 november 2018 om 18:14

“Zijn de mensen alhier nu blij met de uitverkiezeing van deze Bolsenaro, waarbij vergeleken Trump een koorknaap is.”

Ik heb het ook niet zo op figuren die op een koorknaap lijken; voor je het weet schieten ze door naar de top (Klaver, Jesse en wat zangeressen uit het koor).

Ik denk dat je de toestand in Brazilië en de VS niet kunt vergelijken en ook de personages Bolsenaro en Trump kunnen moeilijk in een NL-context geplaatst worden.

Ik heb vind wel dat er in NL mensen nodig zijn die valse beloften en integriteit aan de kaak stellen en het kneuterige, knullige beleid op alle fronten gaan bijsturen.

Dan zijn NL-versie van Bolsenaro en Trump welkom.

Boels wellicht kun je eerst eens wat verdiepen in ‘Brazilie’ energie, ecologie, corruptie, prijzen van fossiele brandstoffen enz.

Wellicht dat je dan toch snel op je schreden terugkomt met die ‘kwoot’ de Nederlandse versie is welkom.

Je weet echt niet aar je het over heb en enig inzicht is toch wel echt de basis van een zinnige diskussie.

Het ontbreekt je werkelijk aan kennis van wat er zich zo afspeelt ten zuiden/ oosten enz van Winterswijk en Baerle Nassau..

Of denk jij soms dat het overal toch een beetje lijkt op jouw natgeregende Vinexwijk met zijn tuintjes en BBQ’s…eh en dat alles opgelost met Le Pen/ Wilders en hun populistische agenda die werkelijk wat betreft de relatie tussen energie en economie op helemaal niets gebaseerd is.

@gerard d’Olivat 7 november 2018 om 19:00

Verdieping kan nooit kwaad, maar is het altijd zinvol?

Ik heb geen stemrecht in Brazilië/VS, alleen de buitenlandse politiek van die landen is echt van belang.

Het wijzen met vingertjes over de toestanden daar is nogal makkelijk en het haalt niets uit.

Misschien geeft het een goed gevoel.

Velen ruiken en grijpen naar de macht en als er te weinig tegenkrachten zijn wordt het bruut en gewelddadig.

Sommigen zijn in staat het brute en wezenlijk gewelddadige mooi te verpakken (Crisis en Herstelwet, uitsluiten kernenergie bij klimaatbeleid, afschaffen van een raadgevend referendum).

Zoiets als knollen en citroenen in een vioolkist.

En als de gevestigde politiek weigert te luisteren naar de kiezers dan gaat de populatie richting luisterend oor.

Wat is er mis met “vox populi”.

laatste . = ?

Voor mij is 1 ding in ieder geval heel erg duidelijk.

Henk DJ van der Heijden is een masochist.

Voor de rest ben ik voorstander van een goed milieu.

Wel ben ik benieuwd of onze aarde 10 miljard mensen aankan .

Johan,

Ik denk dat de aarde dat aankan mits er voldoende energie aanwezig is. Dat lukt niet met windmolens ed.

Met alleen ‘groene’ energie gaat het niet lukken en zal het grote sterven beginnen. Maar dat zal niet gebeuren, voor die tijd zijn alle ‘groene’ politici en hun meelopers in een mooi celletje gezet.

Boels er is niets mis met de ‘stem van het volk’.

De vraag is alleen of de ‘stem van het volk’ energie problemen weet op te lossen die laat ik zeggen de D66/VVD/GL elite in hun machts arrogantie wel even denkt te kunnen oplossen.

Laat ik eens een voorbeeld geven.

Op 16 november wordt er hier in Frankrijk een totale blokkade afgekondigd van steden en wegen agv de sterk stijgende brandstofprijzen. Het nieuws gaat hier te lande over niets anders.

Die prijsstijgingen zijn net als overal in de wereld het gevolg van de stijgende prijzen van olie en gas nog versterkt door belastingen. Lees maar even gemakshalve ‘het kwartje van Kok zaliger’.

Dat wordt natuurlijk een commotie van belang met Macron in de hoofdrol. Want ja per januari worden er nieuwe belastingen verwacht op diesel en Euro. Je moet per slot ergens je belastinginkomsten vandaan halen.

We leven trouwens in het kernenergieland in de EU bij uitstek, maar dat terzijde.

Tja die stijging van de fossils gaat de gemiddelde Fransman, echt een groot land, zonder wegenbelasting! maar met veel kilometers per jaar zo’n eh 1500 euro per jaar kosten.

Dat is dan direct, effe afrekenen aan de pomp, de gas en olieboer!

Het aantal gezinnen dat een beroep gaat doen op ‘energiebijstand’ is ongeveer 6 miljoen! (alle Nederlandse gezinnen bij elkaar!) Dan heb ik het nog niet eens over de indirecte kosten stijgingen van producten divers tgv de stijgende vervoerskosten….

Tja hoe de ‘populisten’ en de ‘stem van het volk’ dat tij denken te keren, ik heb geen idee?

Nu heb je Bolsonaro die schijnt populistisch te zijn en hij heeft een hekel aan homo’s en vrouwen die moeten maar ‘gedienstig’ zijn. Dan heb je in Mexico die met dezelfde problemen kampen als Brazilie een omgekeerde populistische premier, die is dan weer ‘links’. Afijn de problemen zijn hetzelfde. De een is voor ‘privatisering’ (Brazilie) de ander voor terug draaiing van de privatisering (Mexico)

Nou nu jij weer Boels.

Hoe denk jij dat ‘de populisten’ de energieprijzen op een welvaartsniveau weten terug te brengen?

@gerard d’Olivat 7 november 2018 om 20:53

Je haalt mij wel uit mijn ritme ;-)

Ik heb eigenlijk niets met politiek, de laatste keer heb ik uit arrenmoede (of was het narrenmoede?) gestemd op de (nu) ongevaarlijke Christen Unie omdat de kandidaten naar zeggen dagelijks vragen om vergeving van de zonden.

Die bezigheid leek mij bij uitstek geschikt voor politici.

Ik volg de politiek wel (live-beelden 2de en 1rste Kamer op de achtergond), maar luisteren naar klassieke muziek bevalt beter (naast helende stilte).

Elke politicus zou er naar moeten streven om populist te zijn, d.w.z. luisteren en verklarend naar de kiezer toe.

Helaas zijn oude stokpaardjes koppig, willen niet achter de wagen gespannen worden en dan is een halfzacht compromis snel geboren mits het stokpaardje tot fokken bereid is met “het nieuwe”.

Wij noemen dat polderen, feitelijk een kruising tussen wat zou moeten en oeroude emoties.

Naast belastingen (voor openbaarbestuur, veiligheid, onderwijs, ..) zijn er ook belastende heffingen; die zijn (oorspronkelijk) bedoeld ter sturing van door politici ongewenst gebruik.

Belast je direkt of indirekt vervoer waar openbaarvervoer ontbreekt of gebrekkig is dan schep je een probleem.

Een populist (de echte politicus) zal daar wars van zijn en dan bezuinigen op overdaad of een onschuldiger heffing introduceren (zoals rekeningrijden in steden).

Energie-armoede is pas echt armoede.

Waarom de salarissen en uitkeringen niet zodanig zijn zodat energie-armoede voorkómen wordt is mij een raadsel (ook in NL); de kosten van het rondpompen van toeslagen zijn aanzienlijk en werken stigmatiseren in de hand.

De Franse situatie volg ik niet intens; Macron lijkt een populist, hem ontbreekt echter “grandeur” (De Gaulle: l’Etat c’est moi).

Wel mooie herinneringen: vakanties, een zeer vroege liefdesrelatie (ik reed privé daarom 100.000km/jaar; er was toen sprake van een afkoelend klimaat, maar niet in Parijs ;-) )

Boels, mooie reactie omdat je in al het gedoe mens blijft: “maar luisteren naar klassieke muziek bevalt beter (naast helende stilte).”

De mens is niet alleen logica gelukkig…

De mens is meer en verdient beter dan dat.

Verblijven in logica is wat mij betreft de hel op aarde.

De nuttigheid ervan is één ding, maar verwar logica niet met wijsheid in kader een zich voltrekkend leven.

Gerard, benzine is spotgoedkoop in Frankrijk merkte ik afgelopen zomer. Fransen staken om het minste of geringste.

Gerard d’Olivat

Misschien zou het helpen als op de pomp telkens weer duidelijk werd gemaakt wat de kale brandstofprijs is en de prijs inclusief belastingen. Niet de brandstof is duur, maar de heffingen erop. Belasting moet worden betaald om allerlei maatschappelijk noodzakelijke voorzieningen te betalen. Die belasting wordt uiteraard geheven op die producten en diensten waar we allemaal massaal gebruik van maken. Waarbij een deel van het voedselpakket wordt ontzien. Maar langzamerhand ontbreekt het overzicht en volgen we allemaal slaafs de verhogingen. De Fransen zijn kennelijk wél allert. Maar zou er iets veranderen?

@Olivat Vervelend van die prijsstijgingen. Suggereert jij nu dat van nu af aan de prijzen zullen blijven stijgen alsof er al merkbare krapte is doordat brandstoffen echt op raken? Lees dan eerst maar eens het statistical review van BP.

De oliekraan van de OPEC bepaalt de olieprijs, al sinds 1973.

Jeroen

Ga je ook Scheffer even corrigeren als hij weer met zijn 50 mld per jaar komt ?

Of komt dat goed in je ideologische straatje van pas en negeer je dat ?

Maar goed voor een econoom die van mening is dat 69 meer is dan 85 verbaasd me dat niets

Zolang windenergie de hoofdmoot van ”van het gas los” en “duurzaam” Nederland gaat uitmaken is de 50 miljard Eu per jaar de komende 20 jaar nog te laag berekend. De extra kosten van alle nadelen van een incapabel weerafhankelijk moeilijk te balanceren stroomnetwerk en een als gevolg ongeschikt aanbod/vraag energiesysteem door extra groeiende stroomvraag vanuit de industrie en mobiliteit zal er nog zo’n 20 miljard Eu er bovenop komen voor allerlei back-up en nood maatregelen. Laten dan maar meteen besluiten te stoppen met windenergie en per direct belastinggeld te alloceren voor R&D voor Thorium MSR centrales. Climate-control-deniers zullen natuurlijk voor windenergie blijven pleiten.

Steeds vaker blijkt dat, ondanks uitgebreide peer reviews, ook bekende klimaatwetenschappers fouten maken a la Snotneus J.K. met even zo vaak alarmerende gevolgen. Wat bijvoorbeeld te denken van deze: https://wattsupwiththat.com/2018/11/07/oops-the-oceans-are-warming-fast-resplandy-et-al-shows-how-peer-review-can-fail-even-at-nature/

Eigenlijk merkwaardig dat een landje dat best een paar graden warmer kan gebruiken zich zo verzet tegen de natuurlijke klimaatverandering. En dit terwijl men in vele landen waar een paar graden warmer niet prettig zou zijn men helemaal niet bezig is met het klimaat verhaal.

Dat roept toch wel vragen op.